社会聚焦

【Choice杂志】食品责任保险:对特产农作物销售市场的影响

发布时间:2015/01/27

译文:

食品责任保险:对特产农作物销售市场的影响

Kathryn A. Boys

关键词:食品安全,保险,责任,市场,特产农作物

因担忧食品安全,特产农作物近几年销售市场备受影响。美国疾病防控中心(CDC)估计每年发生的4800万起食源性疾病致使128000人住院,3000人死亡(CDC,2012)。当中有确定原因的,46%的疾病与23%的死亡归因于食源性疾病(Painter等,2013)。因确定原因及未知原因造成的食源性疾病每年所产生的全部医疗成本、生产损失、过早死亡成本预计有510亿美元(Scharff,2012)。

为减少上述这些风险,国家及私人部门已经制定了新的条例、认证及标准。所有这些措施中最关键的是于2011年1月将美国食品和药品管理局(FDA)的《食品安全现代化法案(FSMA)》签署为法律。尽管该法案目的在于改善食品安全现状,但部分人认为法案缺乏足够的调研或得出错误的结论(Conroy,2011)。此外,《食品安全现代化法案》特斯特-哈根提案修正案中修改了对中小规模农场的食品安全要求,中小规模农场超过50%的产品直接售卖给消费者、零售商或餐馆。该修正案旨在减少中小生产者的监管负担,但一些买家认为该规定将不能保证中小生产者的食品安全。

进一步说,尽管食品公司可能尽力去达到甚至超过食品安全协议要求的标准,但食物仍可能在上游生产商环节被污染。在这种情况下,最终产品的最后销售商及做促销活动的机构可能需(共同)为污染食品造成的伤害承担损害赔偿责任。因此,目前越来越多的商家要求食品生产者购买食品责任保险(FPLI),倘若因食品消费,食品处理、及生产者食品加工环境、售卖环境、处理条件、分销过程等因素给消费者带来伤害,食品责任保险可提供保护。越来越多的学校、医院、食品零售商、农贸市场在内的大型餐饮服务机构要求其食品供应商购买食品责任保险。

最近在美国东南部开展的几个研究项目总结了特产农作物销售至餐饮服务机构过程中面临的主要问题及食品安全挑战。这些项目从中小型特产农作物农民及购买者和促销商角度调查了销售渠道的限制与挑战。该问题的研究始于对北卡罗莱纳州、南卡罗莱纳州和乔治亚州两大核心群体的调查:(1)农民;(2)食品购买者及销售商。其中,农民群体指出其最关注的问题是:食品安全法规与实践的不确定性和寻找及筹资购买食品责任保险面临的挑战。随后,来自于中小农场、特产农作物销售渠道机构的利益相关者举办了大型会议,来提出和衡量已知挑战的解决办法。

随后对中小型食品生产者、学校和医院等餐饮服务食品购买者开展调查,获取了大量对定性结果的看法。整个南部可持续农业研究与教育(SARE)项目地区(弗吉尼亚州到德克萨斯州的美国东南部地区)的中小型特产农作物农民在线接受调查。来自北卡罗莱纳州、南卡罗莱纳州及乔治亚州的学校和医院等餐饮服务购买者通过邮寄纸质调查问卷的形式做了调查。定性研究阶段、生产者调查和餐饮服务机构购买者的研究方法及调查结果的更多细节问题分别详见Westray(2012),DuBreuil(2013),Nunnelley(2012)。基于这些研究结果开展以下讨论。

食品责任保险需求

确保特产农作物生产者有足够的动力来提供安全的食品是很重要的。文献表明,保险同责任规则相结合旨在减少保险公司承担不断增加风险的动力(道德风险),或改善生产者与保险公司间的信息不对称现状(逆向选择),食品责任保险促进食品安全水平的提高(Tuevey, Hoy, Islam, 2002;Mojduszka, 2004)。然而,在实践中,食品责任保险并未促成以上结果。大量结果表明食品购买者机构和农民市场管理者并未意识到其机构责任的范围(Westray, 2012)。对这些食品购买者及市场营销者来说,据报道,在很多情况下,保险需求由其他群体传闻需求决定,而不是由评估生产者风险及产品风险决定。行业团体及非政府机构(NGOs)并未对食品供应商应购买多少金额的保险提供充分指导。然而,重要的是,相当一部分机构指出食品责任保险目前并不是食品供应商的先决条件,这些机构正在考虑将食品责任保险作为食品供应商的必须条件。

在食品责任保险已经成为先决条件的情况下,所要求的保费却变化较大。针对公立学校、医院餐饮买家的调查报告显示:大部分机构保额要求在100万美元到300万美元之间,但实际的保额在10万美元到500万美元和1000万美元不等(表一)。这些调查结果通常与美国农业部的调查结果一致,即学校的食品责任险因学校所处地域的不同而在10万美元到3百万美元不等(美国农业部农业市场服务,2011)。

表一 食品责任保险要求保额—基于直接将产品售卖给学校与医院的农场调查

|

要求保额 |

公立学校(K-12) |

医院 |

|

|

调查对象 |

百分比% |

调查对象 |

百分比% |

|

低于100万美元 |

10 |

20 |

3 |

15.8 |

|

100万美元-300万美元 |

35 |

70 |

11 |

57.9 |

|

300万美元-500万美元 |

3 |

6 |

2 |

10.5 |

|

500万美元-1000万美元 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

15.8 |

|

高于1000万美元 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

不需要购买食品责任保险 |

5 |

|

3 |

|

|

不清楚 |

51 |

|

25 |

|

|

调查者人数 |

106 |

|

51 |

|

注:百分比数值是通过计算了解食品责任保险所要求保额的调查者

在很大一部分案件中,买家不知道机构的保额要求。进一步说,有意思的是,所有医院和80%的学校在不知道要求的保额的情况下,表明他们会要求直接与他们交易的农场提供食品责任保险。

更大一些的买家,比如地区或全国性的食品零售商,据称其要求的保额在200万美元到500万美元不等。不出所料,这些市场,买方公司的规模与食品责任保险额度要求是有联系的。

购买食品责任保险

近期在美国东南地区的一个对小中型农场的调查显示,38%的受调查者(n=258)表示他们目前已购买食品责任保险。他们购买保险的动机不同,但通常是因为担心责任后果(74%的保单持有人),对买方的要求(32%),或者是他们的市场营销策略(14%)。后面的这个结果尤为重要。据公司称,他们购买这种保险是为了提升公司的声誉(20.2%),增加产品价值(7.1%),帮助他们从竞争者中脱颖而出(5.1%)。在食品责任保险被广泛应用之前,被投保的产品将有效地成为公司营销的手段。

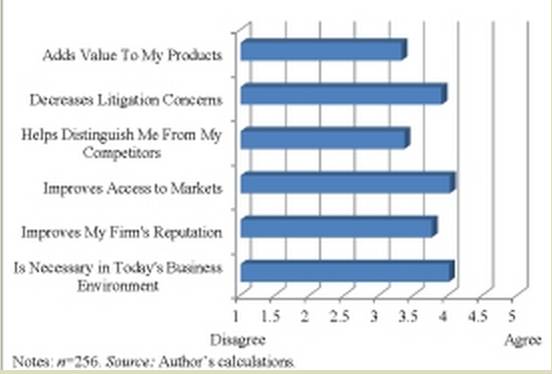

农民关于食品责任保险的意见进一步加强了对该产品多功能性的感知。他们在表明同意购买食品责任保险时,关于它在减少诉讼问题和市场准入的作用上,却引起强烈的意见讨论(表一)。然而重要的是,在这里营销策略再次产生了影响,特别是十分肯定了保险能为一个公司带来声誉。

表一 中小型规模特产农作物农民关于食品责任保险的意见

购买食品责任保险通常不是没有其自身挑战的。提供保险采购流程者(n = 88)中的许多(26.1%)指出识别投保这种风险的公司是一种挑战。农民称他们平均联系了2.4个公司以期获得保险费报价;大约一半的保险公司无法提供食品责任险政策报价。现投保的农民称把保费增加到他们现有的保单包(9.0%)中会相对比较容易。

然而,食品责任保险的可用性存在很大的跨地区差别。许多买家(9.6%)称在获得一家报价前接触了5个或5个以上保险公司。还有几个农民表示,他们最终雇佣了一个保险经纪人或寻求国家农业部门协助来帮助他们识别提供本保险产品的公司。其他指出采购的挑战是保险的费用(7.9%)、低覆盖率限制,与除外责任(例如“传染病”)。这些都是许多保单的标准要求。

从这些调查中可知,食品责任险是特产农作物生产者最关心也是最不了解的商业问题。通常来说,在给出更多地信息之前,有许多关于食品责任保险和标准责任险之间区别的疑问。农民们相对来说并不了解他们对该险的需求以及假如需要的话,也不了解该保险的额度是多少。还有,一些受调查者称因他们有良好的田间处理措施,他们不需要这种保险。显然,对这个话题,有很大必要作更大的扩延研究。

食品责任险市场

对中小型特产农作物生产者来说,食品责任险市场还处于起步阶段。其对保险额度的要求因人而异,并且根据我们的定量研究(Westray, 2012)发现,保额要求与产品引起食源性疾病的风险并没有联系。并且,提供保险产品者并不非常熟悉与各种特产农作物相关的食源性疾病。因此,有着类似风险和产出的农场及类似保险额度,所需的保险费大有不同。这一问题也仍需要扩展性研究以及保险行业的教育培训。

还有一点也很重要,即产品责任险的条款和行政措施也和农作物保险不同。农作物保险是通过公私伙伴关系提供的。私人的保险公司出售并提供农作物保险的服务。中央农作物保险公司再次确认这些保单。农业部管理并监督由中央农作物保险公司授权的所有项目。为了运行这些项目,每个州都被授予了一定限制的监管责任(Klein and Krohm, 2008)。相反,美国没有统一、完整地联邦法来治理产品责任,包括农场和食品产品(Buzby and Frenzen, 1999)。取而代之的是每个州有对产品责任的立法权。因此,食品责任保险的管理规则以及由食源性疾病引起的法律诉讼由各州法律规定,大相径庭。

食品责任保险具体投保额度也存在着很大的差别。以农场主、房主、商业、以及其他索赔和责任事件为投保标的的保险是一些比较常见的业务。然而这些业务额度类别上有所不同。每个事件的保险额度或每年的额度可能有限制,并且因业务不同而不同。每次事件保险额度或者每年的保险额度均可能受限制。这些细节在发生食品安全事件中显然非常重要。

不同保险间保额不同,这使得我们很难分清食品责任保险的附加保额。事实上,在最好情况下大多数生产商只能通过保险费率反映他们全部责任保险。Holland(2007)在研究这个问题上取得了一些进展。基于保险提供者在1998年进行的一项非正式调查,其报告中提到,对100万美元的保险额度,每年食品责任保险保费从500美元到20000美元不等。100万美元保险额度,食品责任保险平均保费为3000美元。影响保费最重要的因素是:销售总额或年度薪酬水平、声明(声明历史)、投保水平、产品类型、市场类型、以及撤回计划。食品责任保险并没有“标准费率”。实际保费依赖于产品具体特征及公司增值和市场计划。

尽管获得保费报价时有困难,但是我们结果表明货比三家是值得的。许多例子都表明具有相似风险的保险,费率却大不相同。同样,生产者们也表示相同地方食品责任保险保费也有很大差别。一位受调查者称,假如给他/她的农场投保100万美元,保费从250美元到1500美元不等。或者,生产者可以加入市场或分销系统,该系统为其成员提供食品责任保险作为服务。Markley(2010)记录了几个这样的案例。一些受调查者说他们被要求参加食品责任保险团体以此作为在某些农贸市场出售产品的条件。然而,虽然这些团体提供保险,但只为通过这些团体销售的产品提供保险。

结论

食源性疾病爆发的财政负担历来都是由有过错嫌疑或实际过错的公司来承担。随着可追溯实践的提高,食品安全事件的成本变得越来越有针对性,也给相应公司带来了更大的负担。面对此种事件,在努力减少潜在责任时,越来越多的公司要求供应商购买食品责任保险。然而,这一要求对特产农作物生产者的成功和利润有着重要的影响。生产者们购买这种保险产生了新的,通常是巨大的固定成本。整个市场营销渠道可能会对没有购买这种保险的生产者紧闭销售大门。这个问题对中小型生产者来说尤为担忧,这些农民通常缺少资金,而且由于其相对较小的生产量和物流的限制,进入许多机构或商业餐饮渠道本身就已经很困难。因此,食品责任险的低效很可能会增加特产农作物的成本,同时还会限制生产者通过直接的市场渠道销售产品的能力。因此,收入和利润可能会减少,在一些情况下部分生产者的活力可能受到影响。

当然,中小型农场也可以选择不投保。然而,即使食品责任保险不是必需的,一次食源性疾病的爆发可能会对中小型农场自身以及周边的社区产生重大的经济影响。 Buzby,Frenzen,和Rasco(2002)发现陪审团裁决的食物中毒案件中,平均赔偿金额已达到25560美元。如果没有保险,一件食源性疾病事件可以压垮一个商家。进一步说,这样的事件还会对当地食物系统消费者信心造成重大的负面影响。考虑到投资的巨大流动性和精力,以增加消费和扩大从中小型生产者那采购新鲜水果和蔬菜的来源,比如,美国农业部妇女、婴儿和儿童(WIC)农贸市场营养计划(FMNP),美国农业部农场到学校计划等,食品责任保险市场效率低下引起的对特色作物生产者的膨胀成本和限制市场准入直接与公众利益和福利有关。我们需做更多地努力使食品责任保险这个新兴市场中的利益相关者更多地了解该保险背后真正的风险。

更多信息参考:

[1] Buzby, J.C., and Frenzen, P.D. (1999). Food safety and product liability. Food Policy, 24(6), 637-651.

[2] Buzby, J.C., Frenzen, P.D., and Rasco, B. (2002). Jury decisions and awards in personal injury lawsuits involving foodborne pathogens. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 36(2), 220-238.

[3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2012). Foodborne Diseases Centers for Outbreak Response Enhancement – About FoodCORE. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/foodcore/about.html.

[4] Connally, E.H. (2009). Good food safety practices: Managing risk to reduce or avoid legal liability, CTAHR FST-32. University of Hawaii at Mãnoa College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources. Availableonline: http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/FST-32.pdf.

[5] Conroy, P. (2011). 2011 Consumer food and product insights survey. Deloitte. Available online: http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-UnitedStates/Local%20Assets/Documents/Consumer%20Business/us_cp_2011foodsafetysurvey_041511.pdf.

[6] DuBreuil, K.M. (2013). Exploring potential innovative marketing approaches for US agribusinesses (M.S. Thesis). Virginia Tech Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, Blacksburg, Virginia.

[7] Holland, R. (2007). Food product liability insurance (CPA Info #128). University of Tennessee Center for Profitable Agriculture.

[8] Klein, R.W. and Krohm, G. (2008). Federal crop insurance: The need for reform. Journal of Insurance Regulation, 26(3), 23-63.

[9] Markley, K. (2010). Food safety and liability insurance: Emerging issues for farmers and institutions. CFSC Report, funded by USDA Risk Management Agency. December 2010.

[10] Mojduszka, E.M. (2004, August 1-4). Private and public food safety control mechanisms: Interdependence and effectiveness. Annual AAEA meeting, Denver, Colorado.

[11] Nunnelley, A.R. (2012). Procuring and tracing produce from small- and medium-scale farmers for use in institutional foodservice operations in NC, SC and GA (M.S. Thesis). Clemson University Department of Food, Nutrition, and Packaging Sciences, Clemson, South Carolina.

[12] Painter, J.A., Hoekstra, R.M., Ayers, T., Tauxe, R.V., Braden, C.R., Angulo, F.J., and Griffin, P.M. (2013). Attribution of foodborne illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths to food commodities by using outbreak data, United States, 1998-2008. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 19(3), 407.

[13] Scharff, R.L. (2012). Economic burden from health losses due to foodborne illness in the United States. Journal of Food Protection, 75(1), 123-131.

[14] Skees, J.R., Botts, A., and Zeuli, K.A. (2001). The potential for recall insurance to improve food safety. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 4(1), 99-111.

[15] Turvey, C.G., Hoy, M., and Islam, Z. (2002). The role of ex ante regulations in addressing problems of moral hazard in agricultural insurance. Agricultural Finance Review, 62(2), 103-116.

[16] United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Marketing Service. (2011). USDA Farm to School Team – 2010 Summary Report. Washington, DC. Available online: http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/f2s/pdf/2010_summary-report.pdf

[17] Westray, L. (2012). Serving as suppliers to institutional foodservices: Supply chain consideration of small and medium scale specialty crop producers (M.S. Thesis). Clemson University Department of Applied Economics and Statistics, Clemson, South Carolina.

原文:

Food Product Liability Insurance: Implications for the Marketing of Specialty Crops

Kathryn A. Boys

JEL Classifications: Q12, Q13, G22

Keywords: Food safety, Insurance, Liability, Marketing, Specialty Crops

The growth of the market for specialty crops may have been hindered in recent years by concerns about food safety. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 48 million instances of foodborne illnesses occur each year resulting in 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths (CDC, 2012). Of those with an identified cause, 46% of illnesses and 23% of deaths are attributable to illness acquired through produce consumption (Painter et al., 2013). Overall medical costs, productivity losses, and the costs of premature deaths due to identified and unspecified cases of foodborne illness have recently been estimated to be a staggering $51.0 billion annually (Scharff, 2012).

To mitigate these risks, public and private sectors have responded with new regulations, certifications, and standards. Key among such initiatives is the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) signed into law in January 2011. While this Act is intended to improve food safety, some argue it lacks sufficient reach or addresses the wrong issues (Conroy, 2011). Further, the FSMA’s Tester-Hagan Amendment modified food safety requirements for small-and medium-scale (SMS) farms that locally sell more than 50% of their produce directly to consumers, food retailers, or restaurants. While this exemption is intended to reduce the regulatory burden on small- and medium-size producers, some food buyers feel that, with this exception, there is insufficient assurance of food safety practices from SMS producers.

Further, although firms may be duly diligent and meet or even exceed accepted food safety protocols, food could still become contaminated by an upstream supplier. In such cases, the final seller of the finished product and the organizations facilitating the sale of that product may be held (jointly) liable for damages resulting from that hazard. As a result, an increasing number of businesses now require food suppliers to carry food product liability insurance (FPLI) to provide protection in the event of injury to a user that may arise from the consumption, handling, use of, or condition of products manufactured, sold, handled, or distributed by producers. Larger foodservice establishments including schools and hospitals, food retailers, farmers’ markets, and kitchen incubators are increasingly requiring their suppliers, or those who supply through them, to carry this insurance product.

General barriers and food safety challenges in marketing specialty crops to institutional foodservice establishments have been recently explored through several research projects in the U.S. Southeast region. These projects examined marketing channel constraints and challenges from the perspectives of both SMS specialty crop farmers, and those buying and facilitating the sale of these crops. Study of this issue began with two series of focus groups held in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia with groups of (1) farmers, and (2) food buyers and market facilitators. Uncertainty concerning food safety regulations and practices, and challenges with finding and financing FPLI are among the key concerns noted by farmers. Large group meetings were then held with stakeholders from throughout the SMS farm-to-institution specialty crops marketing channel to identify and evaluate possible solutions to the identified challenges.

Surveys of SMS producers, and school and hospital foodservice buyers were subsequently conducted to obtain quantitative insight into the qualitative findings. SMS specialty crop farmers from throughout the Southern-Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program region (the Southeastern United States includes states from Virginia to Texas) were surveyed electronically. Responses from school and hospital foodservice buyers from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia were collected via a mailed paper survey. Additional details of the research methodology and results from the qualitative research phase, the producer survey, and the institutional foodservice buyer survey are documented in Westray (2012), DuBreuil (2013), and Nunnelley (2012), respectively. The following discussion draws upon results from these studies.

The Demand for Food Product Liability Insurance

It is important to ensure that specialty crop producers are sufficiently motivated to provide safe food products. Literature shows that, in conjunction with liability rules designed to decrease incentives for insured firms to take on increased risk (moral hazard), or which reduce risk information asymmetry between producers and insurers (adverse selection), insurance can provide incentives to supply efficient levels of food safety (e.g., Turvey, Hoy and Islam, 2002; and Mojduszka, 2004). In practice, however, it is unlikely that this insurance product will motivate these outcomes. Qualitative results indicate that institutional food buyers and farmers’ market managers are generally unaware of the extent of their organization’s liability (Westray, 2012). For these buyers and market facilitators, in many instances it was reported that insurance coverage requirements were determined through hearsay of requirements by other groups rather than any assessment of a producer’s or a product’s risk. Industry groups and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have not offered sufficient guidance concerning what coverage amounts should be required of suppliers. Importantly, however, a significant proportion of organizations who noted that FPLI is not currently a supplier prerequisite are considering instituting it as a requirement.

In cases where FPLI is already an established requirement, the amount of required coverage was found to vary considerably. Surveys of public school and hospital foodservice buyers reported that a majority of organizations had coverage requirements between $1 million and $3 million, but that this amount ranged from $100,000 to between $5 million and $10 million (Table 1). These results are generally consistent with findings of a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) study which found that food product liability insurance coverage requirements for schools varied by school district and were between $100,000 to $3 million (USDA Agricultural Marketing Service, 2011).

In a substantial number of cases, buyers did not know their organization’s coverage requirements. Further and interestingly, all hospitals and 80% of schools who reported that they did not know what amount of insurance was required, indicated that proof of product liability insurance would be required from any farms selling directly to them.

Larger buyers, such as regional or national food retailers, were reported to have insurance coverage requirements ranging from $2 million to $5 million. Unsurprisingly, in this market there appears to be a positive correlation between the size of the buying firm and its FPLI coverage requirements.

In a recent survey of small- and medium-scale specialty crop farmers in the U.S. Southeast region, 38% of respondents (n=258) indicated that they currently have FPLI. Their motivation for purchasing this insurance product varied, but generally was due to liability concerns (74% of policy holders), buyer requirements or requests (32%), or as an intentional part of their marketing strategy (14%). This latter result is particularly important. Firms reported that they viewed purchasing this insurance as helping to support their firm’s reputation (20.2%), adding value to their products (7.1%), and helping to distinguish their products from that of their competitors (5.1%). Thus until it is more widely adopted, this insurance product may effectively be included as a component in a firm’s marketing or differentiation strategy.

Farmer opinion regarding this insurance further reinforces the perceived multi-functionality of this product. When indicating the extent to which they agreed with statements about FPLI, responses concerning its role in decreasing litigation concerns and market access, elicited some of the strongest opinions (Figure 1). Importantly, however, here again marketing strategy impacts, and in particular the assurance that this insurance is thought to provide for a firm’s reputation, were strongly rated.

Procuring this insurance is often not without its own challenges. Of those who provided information regarding their insurance purchasing process (n=88), many (26.1%) noted challenges in identifying firms that would insure against this risk. On average farmers reported contacting 2.4 companies to get insurance premium quotes; about half of these companies were not able to provide FPLI policy quotes. Farmers who are currently insured by companies that offer this form of insurance though, reported it was relatively easy to add this coverage to their existing policy bundles (9.0%).

Availability of this insurance coverage, however, varies considerably across regions. Many buyers (9.6%) reported approaching five or more insurance companies before they were able to obtain a single quote. Further, several farmers indicated that they ultimately hired an insurance broker or approached state departments of agriculture for assistance in identifying companies which offered this insurance product. Other noted procurement challenges were the expense of this insurance (7.9%), low coverage limits, and exclusions (e.g. for “communicable diseases”) which were standard on many policies.

From these studies we also learned that food product liability insurance was noted among the most concerning and least understood business issues among specialty crop producers. In general, prior to providing respondents additional information, there was considerable confusion regarding the difference between FPLI and standard liability insurance. Farmers are relatively uninformed about the need for this insurance and to what extent, if any, they have coverage for this type of liability. Moreover, several respondents stated that they would have no need for this insurance due to their good on-farm handling practices. Clearly there is much need for additional Extension efforts on this topic.

Food Product Liability Insurance Market

The FPLI market for SMS diversified specialty crop producers is in its infancy. The insurance coverage being required by buyers of specialty crops varies considerably, and findings from our qualitative research (Westray, 2012) suggests coverage requirements are not correlated with the true risk of foodborne disease of the products being purchased. Further, those supplying this insurance product are not sufficiently familiar with foodborne disease risks associated with various specialty crops. As a result, insurance premiums have been reported to vary widely for similar coverage for farms that have very similar risk and output profiles. Here also there is a need for Extension efforts and insurance industry education.

It is important to note also that the provision and administration of product liability insurance is very different than that of crop insurance. Crop insurance is offered through a private-public partnership. Agents of private insurance companies sell and service crop insurance policies. The Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC) reinsures these policies and the USDA Risk Management Agency (RMA) administers and oversees all programs authorized under the FCIC. For this program, a limited amount of regulatory responsibility is delegated to each state (Klein and Krohm, 2008). In contrast, there is no uniform, comprehensive Federal law governing product liability, including that for farm and food products, in the United States (Buzby and Frenzen, 1999). Instead, individual states have jurisdiction over product liability law. As a consequence, the regulations governing FPLI and legal actions arising from foodborne illnesses that are governed by state laws often vary considerably.

The specific insurance lines of business under which FPLI is covered varies considerably as well. Farm owners multiple peril, homeowners multiple peril, commercial multiple peril, other liability - occurrence, and other liability - claims are some of the more common business lines under which product is insured. These lines of business differ, however, in the categories of items they cover. Coverage per occurrence or per year may be limited and is likely to vary across lines. Such details would clearly be important in the event of a food safety incident.

Accounting for coverage differences across and within various insurance lines makes it difficult to disentangle the premium amount specifically attached to FPLI. Indeed, when asked, at best most producers could cite only rates reflecting their whole bundle of liability insurance. Holland (2007) made some progress in exploring this issue. Based on an informal survey of insurance providers conducted in 1998, he reported that the annual premiums for FPLI ranged from $500 to $20,000 for a $1 million policy. The average food product liability premium was found to be $3,000 for a $1 million annual policy. The most significant factors contributing to the premium charged were: level of gross sales or annual payroll, prior claims (claims history), level of coverage, type of product, type of market, and recall plan. There were no “standard rates” for liability coverage for food products. The actual premium depended on the many “specific” characteristics of the product and the firm’s value added and marketing plans.

Despite the difficulty often reported in obtaining multiple quotes, our results suggest that it does pay to shop around. Many anecdotal examples were shared of the significant variance in quoted rates for farms with very similar risk profiles. Similarly, significant premium variance was noted by producers in obtaining multiple quotes for the same location. One respondent reported, for example, that quotes for the same $1million coverage on his/her farm varied from $250 to $1,500. Alternatively, producers could join a marketing or distribution network which offers this insurance as a service to its members. Markley (2010) documents several such case examples, and several respondents noted that they were required to participate in a group FPLI policy as a condition of selling at certain farmers’ markets. When insurance is provided through such groups, however, it provides coverage only for products marketed through those organizations.

Concluding Observations

The financial burden of foodborne illness outbreaks has historically been borne by firms in both suspected and the actual industries at fault for the incident. Increased use of traceability practices allows the cost of food safety incidents to be more targeted and increasingly borne by the implicated firms. In an effort to mitigate against potential liability in the face of such an incident, firms are increasingly requiring that their suppliers have food product liability insurance coverage. This requirement, however, has important implications for the success and profitability of specialty crop producers. Producers purchasing this insurance incur a new and oftentimes substantial fixed cost. Entire marketing channels may be closed to those who do not or cannot purchase such insurance. These concerns are particularly important for small- and medium-sized producers. These farmers frequently are financially constrained and, due to their relatively small volume of production and logistic constraints, already may have difficulty accessing many institutional or commercial foodservice markets. Therefore, inefficiencies associated with food product liability insurance could effectively increase the cost of specialty crop production, while at the same time limiting the ability of producers to sell products even through direct marketing channels. As a result, revenues and profitability could decline and, in some cases, viability of some producers could be affected.

There is, of course, the option for SMS farms to remain uninsured. Even if FPLI was not a requirement, however, a single incident of foodborne illness outbreak attributed to a SMS farm would likely have serious negative financial impacts on both the originating farm and those in the surrounding community. Buzby, Frenzen, and Rasco (2002) found that where awards were made in jury adjudicated cases of food poisoning, the median amount awarded was $25,560. Without insurance then, a single foodborne illness incident attributed to a SMS farm could foreseeably force a business shutdown. Further, such an event could also have significant and negative impacts on consumer confidence in that locality’s food system. Given the significant mobilization of investment and effort dedicated to increase the consumption and sourcing of fresh fruits and vegetables from SMS producers (e.g. USDA Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Farmers Market Nutrition Program (FMNP), USDA Farm to School Grant Program), inflated costs and limiting market access for specialty crop producers due to liability insurance market inefficiencies is directly counter to the public interest and welfare. Efforts are needed to better inform all stakeholders in this emerging market about the real risks associated with food product liability.

For More Information

[1] Buzby, J.C., and Frenzen, P.D. (1999). Food safety and product liability. Food Policy, 24(6), 637-651.

[2] Buzby, J.C., Frenzen, P.D., and Rasco, B. (2002). Jury decisions and awards in personal injury lawsuits involving foodborne pathogens. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 36(2), 220-238.

[3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2012). Foodborne Diseases Centers for Outbreak Response Enhancement – About FoodCORE. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/foodcore/about.html.

[4] Connally, E.H. (2009). Good food safety practices: Managing risk to reduce or avoid legal liability, CTAHR FST-32. University of Hawaii at Mãnoa College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources. Availableonline: http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/FST-32.pdf.

[5] Conroy, P. (2011). 2011 Consumer food and product insights survey. Deloitte. Available online: http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-UnitedStates/Local%20Assets/Documents/Consumer%20Business/us_cp_2011foodsafetysurvey_041511.pdf.

[6] DuBreuil, K.M. (2013). Exploring potential innovative marketing approaches for US agribusinesses (M.S. Thesis). Virginia Tech Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, Blacksburg, Virginia.

[7] Holland, R. (2007). Food product liability insurance (CPA Info #128). University of Tennessee Center for Profitable Agriculture.

[8] Klein, R.W. and Krohm, G. (2008). Federal crop insurance: The need for reform. Journal of Insurance Regulation, 26(3), 23-63.

[9] Markley, K. (2010). Food safety and liability insurance: Emerging issues for farmers and institutions. CFSC Report, funded by USDA Risk Management Agency. December 2010.

[10] Mojduszka, E.M. (2004, August 1-4). Private and public food safety control mechanisms: Interdependence and effectiveness. Annual AAEA meeting, Denver, Colorado.

[11] Nunnelley, A.R. (2012). Procuring and tracing produce from small- and medium-scale farmers for use in institutional foodservice operations in NC, SC and GA (M.S. Thesis). Clemson University Department of Food, Nutrition, and Packaging Sciences, Clemson, South Carolina.

[12] Painter, J.A., Hoekstra, R.M., Ayers, T., Tauxe, R.V., Braden, C.R., Angulo, F.J., and Griffin, P.M. (2013). Attribution of foodborne illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths to food commodities by using outbreak data, United States, 1998-2008. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 19(3), 407.

[13] Scharff, R.L. (2012). Economic burden from health losses due to foodborne illness in the United States. Journal of Food Protection, 75(1), 123-131.

[14] Skees, J.R., Botts, A., and Zeuli, K.A. (2001). The potential for recall insurance to improve food safety. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 4(1), 99-111.

[15] Turvey, C.G., Hoy, M., and Islam, Z. (2002). The role of ex ante regulations in addressing problems of moral hazard in agricultural insurance. Agricultural Finance Review, 62(2), 103-116.

[16] United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Marketing Service. (2011). USDA Farm to School Team – 2010 Summary Report. Washington, DC. Available online: http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/f2s/pdf/2010_summary-report.pdf

[17] Westray, L. (2012). Serving as suppliers to institutional foodservices: Supply chain consideration of small and medium scale specialty crop producers (M.S. Thesis). Clemson University Department of Applied Economics and Statistics, Clemson, South Carolina.

网站链接: